The Tale of TANABATA 七夕伝説

The Tale of Tanabata, which originated in China, has been told in Japan for at least 1200 years. The Japanese version tells the story of a cowherd (Kengyū in some versions, Hikoboshi in others, as the star Altair), and the Weaving Princess (Orihimé, as the star Vega). They were so enamored with each other, the legend goes, that their work suffered. As a result, the two lovers were banished to opposite ends of the firmament. After frequently beseeching the gods to reunite them, their wish was granted: a brief meeting would be permitted, albeit, once a year.

This meeting occurs on the seventh day of the seventh lunar month — the day Tanabata is celebrated in Japan. Today in most parts of Japan the festival is celebrated on July 7th. But some parts of Japan, like Sendai, use the old koyomi almanac which puts the festival in August.

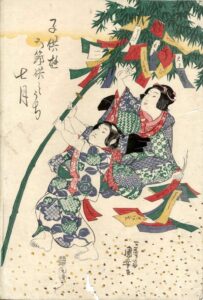

Making wishes, and writing them on tanzaku (narrow strips of colored paper) that get hung on branches of young bamboo, has become part of the Tanabata (Star Festival) as it is practiced today. Above, school children admire the decoration of their wishes that their teachers tied to sasa no ha branches of young bamboo. The custom of writing wishes on tanzaku is well established. Here, a scene from the Edo period.

SŌMEN, Festive Noodles

Sōmen noodles are associated with Tanabata in several ways: When set to dry on racks, sōmen noodles look like threads on a loom (the warp and woof of Orihime’s woven cloth) and flowing on the plate the thin noodles resemble the Milky Way (Ama no Gawa 天の川).

Although white sōmen noodles are sold year-round, many summertime packages will include noodles dyed vivid pink (ume, or plum-flavored), bright yellow (egg-enriched, color enhanced by kuchi nashi no mi dried gardenia pods), or deep olive (matcha tea-flavored). The colored noodles enhance the special connection to TANABATA MATSURI, the Star Festival.

Looking for instructions in making sōmen in your kitchen? Visit earlier posts about sōmen and cold noodle salads.