Kagami Mochi 鏡餅

At New Years’ time, the Japanese decorate their homes with a special display called KAGAMI MOCHI. There are many regional variations on the theme but typically two large rounds of omochi rice taffy are stacked with a daidai 橙 (bitter orange) on top. The arrangement is placed on a ritual display stand decorated with leaves and (auspicious) red-and-white paper. All the elements of the display have symbolic meaning, mostly expressed in homonyms. For example, daidai written as 代々 means “generation after generation” so that including the daidai bitter orange in the display alludes to enduring life and continuity.

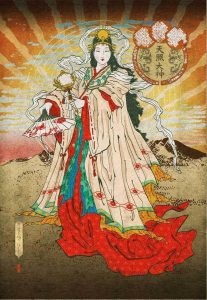

In Japanese Shinto mythology, Amaterasu (Amaterasu-ōmikami 天照大御神), is the ruler of the heavens. The symbol of the diety is a mirror, kagami. Indeed that is why the ritual offering of rice taffy has the name kagami mochi.

Kagami mochi remains on display until January 11 when a ceremony known as kagami-biraki, literally “opening the mirror” takes place. That is when the hardened, crusty mochi cakes are smashed into bits. These are then re-purposed in a variety of ways. For more information, and a recipe for making crispy rice nuggets, visit PROJECT Kagami-Biraki.

Kagami Mochi & Otoshi-dama

The origins of today’s custom of giving otoshi-dama お年玉 money to children at New Years time has connections to kagami mochi. Again, homonyms play a part in understanding the association. In ancient times, the ritual display of omochi was referred to as toshi dama, written with the calligraphy for “year” 歳 and “spirit” 魂 .

The displayed omochi was food for the gods that people believed would visit the house to bestow blessings for the year to come. One explanation of why otoshi-dama became money is that it was the gods’ okaeshi (return gift) for hospitality received when visiting the house. Another explanation links the old-fashioned practice of tasking the oldest son, as representative of the household, to visit the local shrine to pray for the prosperity and wellbeing of the family. The father would then give the son an honorarium for his efforts.

Regardless of the explanation you consider to be most likely, the shift from kagami omochi rice cakes as otoshi-dama to money came about around the start of the Edo Period (1603-1868 AD). Today, school-aged children (from kindergarten to college) are the recipients of otoshi-dama money. Parents, grandparents, aunts and uncles and other adult family friends are the ones who give the money. Sums range from ¥1000 to ¥10,000 (though ¥4,000 and ¥9,000 are avoided because of unlucky associations with the numbers 4 and 9), and the money is always offered folded in a pochi-bukuro envelope.

Download a copy of my January 2026 newsletter about kagami mochi.